Tankar

Widar Andersson

Skribent

•

1 Tim

Innerlig tur att världen har en polis som USA. Dels öppnas en frihetens möjlighet för det plågade iranska folket. Dels spärras en blivande kärnvapenaxel mellan Ryssland och Iran. Med Israels hjälp är nog Trump inställd på att slå ut den nuvarande diktaturen. Hoppas det går vägen. Och hoppas att den oerhört stora iranska diasporan ute i världen kan enas med de inhemska regimmotståndarna och bygga en ny och bättre stat i allians med den demokratiska sfären på vår planet.

Nathalie Rothschild

Poddproducent

•

2 Tim

Oavsett om man är för eller mot det som nu sker så haltar jämförelsen med Irak-invasionen i detta skede på flera punkter, även om retoriken delvis är igenkännlig. I kriget just nu: —Det handlar om luftangrepp, inte markinvasion. —Det handlar om specifika mål - infrastruktur och regimföreträdare - och inte om att ta ut WMD:s vars existens det inte finns bevis för. —Iran har en helt annan ställning och utgör ett helt annat hot idag än Irak då. Det är en regional supermakt som sponsrar terror i hela regionen. —Dessutom startade Iran ett krig mot Israel via sina proxies den 7 oktober 2023. Det är några skillnader jag ser. Kanske finns fler både skillnader och likheter. Vad tycker ni?

Tankar

Pelle Zackrisson

Reporter

•

1 Tim

USA och Israel vare sig vill eller kan själva byta ut den islamiska regimen i Iran. De kan möjligen kratta manegen. Europeiska länder har ett egenintresse i att regimen försvinner. Men regimskiftet måste iranier, både i Iran och exiliranier, aktivt stå för och bistå med.

Senaste nyheterna

12:47

Statsministern: Står bakom det modiga iranska folket

11:49

Flygbolag stoppar flyg till Mellanöstern

11:17

Ayatollah Khameneis palats totalförstört

10:53

Experten: Iran kan svara med attentat i Europa

10:14

Reuters: Flera toppar i Iran döda

09:34

Ryska reaktionen: ”Visar sitt sanna ansikte”

09:26

Explosioner i flera Gulfstater

09:14

Iran avfyrar robotar mot Israel

09:05

Reseavrådan för Israel utvidgad av UD

08:56

Iran: Förbereder svar på attackerna

08:44

Bildt fördömer attacker mot Iran

07:10

Iran har attackerats av Israel och USA

Igår 19:22

Flera länder uppmanar till att lämna Iran och Israel

Igår 19:08

Försvarsmakten bekräftar: Drönaren var rysk

Igår 17:45

Myndighet nämner SD i exempel på desinformation

Igår 17:41

GW anklagar SVT för äppelaktion

Igår 17:21

Runt 40 skadade efter spårvagnskrasch i Milano

Värva tre vänner

Få ett helt år gratis!

Tankar

Göran Fröjdh

Reporter

•

Igår 15:30

Ibland funderar jag på hur det känns för de Teslaanställda som nu är inne på sitt tredje strejkår. Hur fungerar vardagen? Är det inte frustrerande att bara gå att vänta utan att få göra nånting? Får man åka på semester, eller gäller det att vara stand by – beredd att gå tillbaka till jobbet direkt när strejken (kanske) en dag plötsligt är över? Vad händer om den fortsätter ett år till, eller tio? Det skulle vara väldigt intressant att höra någon av dessa långstrejkare berätta. Så är du själv uttagen – eller känner nån som strejkar – hör av dig!

Tankar

Widar Andersson

Skribent

•

Igår 17:01

Yttrandefrihet är väldigt viktigt; en hörnpelare i demokratin. Även om den kan vara väldigt obehaglig ibland. Men demokrati är inte bara behagligt. Jag minns att jag blev förvånad när jag för ganska länge sedan läste det första socialdemokratiska partiprogrammet från 1897. Bland kraven på 8 timmars arbetsdag, allmän och lika rösträtt och religionens transformering till en privatsak fanns kraven på en "fullständig tryck- och yttrandefrihet." Inte konstigt på ett sätt. Den framväxande arbetarrörelsen kämpade mot repressalier och ingripanden från statsmakten. Men konstigt på så sätt att det där med yttrandefriheten liksom försvann när vi som ungdomar i S lärde oss om den tidiga kampen för rösträtt och reglerad arbetstid. En anställd på Migrationsverket och andra statliga myndigheter kan förstås inte bete sig hur som helst. I det här fallet borde dock först och främst universitets - och kommunledningen i Göteborg fått sparken för sin flathet visavi ockupanterna.

Tankar

Jörgen Huitfeldt

Chefredaktör

•

Igår 17:19

Detta fall visar hur svårt det är att leva upp till retoriken om att fler brottslingar ska utvisas. Lätt på pappret men svårt om man ska leva som man lär, d v s inte utvisa folk till situationer där de riskerar förföljelse eller annan omänsklig behandling. Det finns ett pris att betala för en hårdare utvisningspolitik. Är den svenska självbilden redo för att betala det?

Tankar

Linnea Bali

Journalist och poddare

•

Igår 13:46

Stavrum hänvisar till en ”vädjan om medmänsklighet” som anledning till att kasta journalistikens krav på konsekvensneutralitet och allmänintresse åt sidan. Jag håller med om att ett eventuellt självmordsförsök inte är något man lättvindigt bör skriva om. Inte heller i fallet Jagland. Det bör inte påverka övrig rapportering i frågan och säger varken något om eventuell skuld eller oskuld. Men det blir väldigt märkligt när Stavrum vidare i debatten slår fast att Jaglands sjukhusvistelse är ett ”resultat av påfrestningarna” efter avslöjandet om kontakten med Jeffery Epstein. Vad har påfrestningarna bestått av? Ett enormt medialt tryck som Stavrums egen redaktion varit delaktig i. Borde dessa publiceringar aldrig ha skett? Kommer Nettavisans bevakning av denna fråga nu att minska i styrka? Om inte, hur motiverar Stavrum det ”medmänskligt försvarbara” i att utöva påfrestningen som drivit Jagland till sjukhusbädden medan det anses ”omänskligt” att skriva om resultatet? Oförståeligt.

Erik Högström

Fördjupningsredaktör

•

Igår 11:41

Självmord är något av det mest känsliga att skriva om. Det brukar sägas att man ska vara extremt försiktig med att skriva om hur någon begår självmord, eftersom tillvägagångssätt kan smitta. Men att det totala tabut är borta är sunt. Att det inte skrevs brett att Harry Martinsson tog sitt liv genom att hugga sig själv med en sax, utan att det i stället var en sak som bara vissa invigda visste, var märkligt. Men frågan är genuint svår

Staffan Dopping

Poddredaktör

•

Igår 09:30

Självmord har mycket länge varit känsligt när det gäller att publicera uppgifter, även om tabut som var heltäckande började lyftas runt millennieskiftet. Brottaren Mikael Ljungberg och artisten Ted Gärdestad var fall som bidrog till att medierna började skriva klartext om suicid. Men i fallet Jagland, som i alla andra som gäller pressetik, handlar det om att bedöma styrkan i allmänintresset kontra publicitetsskadan. Och för min del är det klart att när en före detta statsminister och generalsekreterare i Europarådet misstänks för grov korruption – då är allmänintresset mycket högt för omständigheter som har anknytning till korruptionsmisstankarna.

Tankar

Tankar

Matilda Berg

Igår 06:11

"En olycka kommer sällan ensam" sägs det ju. Det här ämnet är ytterligare ett exempel på min känsla av att tillvaron blir allt mer komplex. Att som 18-åring – eller nykomling i Sverige – förstå kreditmarknaden kan vara väl mycket att förvänta sig, särskilt under en period i livet då så mycket annat ska falla på plats ... Vi som har barn i den åldern är kanske inte heller alltid medvetna om vad som väntar.

Ludde Hellberg

Vd

•

Igår 05:49

Vad sägs om att föräldrar tar ansvar för att lära sina barn om skulder och ränta, och att barn som blir vuxna tar ansvar för sina egna beslut? Tänk om myndighetspersonerna i texten kunde lägga lite större vikt vid individens ansvar i stället för att peka på de stora stygga strukturerna som gör vanliga oskyldiga medborgare till offer för de elaka storföretagen. Om 99,5% av Klarnas kunder betalar före inkasso kan jag tycka att det känns rätt rimligt att samhället i stort anpassas efter de 99,5 procenten snarare än den halva procenten som inte klarar av att betala sina räkningar i tid. Vad tycker du?

Tankar

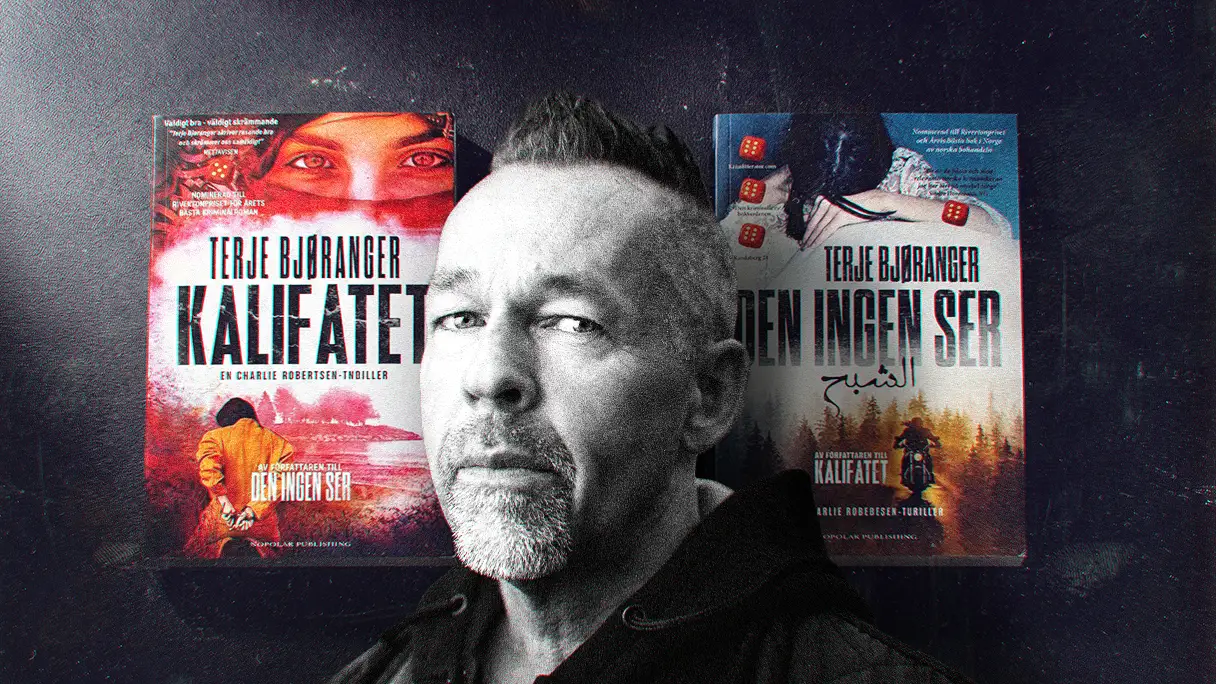

Jesper Andersson

Poddproducent

•

Igår 05:58

Mycket intressant och läsvärd text av Trifa Abdulla. Jag fastnade särskilt för den påminnelse hon väcker: att jihadismen inte bara riktar sig mot ”väst”, utan i hög grad också mot de egna – mot muslimer som uppfattas som avfälliga eller illojala. Samtidigt är det kanske inte så konstigt att det perspektivet hamnar i skymundan. I princip alla uppmärksammade attacker i väst – såväl genomförda som avvärjda – har riktats mot breda civila mål, judiska mål eller symboler för det omgivande samhället, snarare än mot ”de egna”. Med det sagt påminns jag också om att Houellebecqs Underkastelse ligger på mitt nattduksbord. När den är utläst blir det förmodligen en sväng ner till bokhandeln – och Kalifatet.

Tankar

Federico Moreno

Reporter

•

Igår 08:05

Som svartskalle har jag dispens från vintersportstvånget – men jag ska inte kasta pjäxan i skidhuset. Precis som Lundberg skriver utbrister jag högt varannan gång jag handlar på Ica. Jag kan dock rekommendera Fritidsbanken, där alla kan låna sport- och friluftsutrustning gratis i 14 dagar. I en kort passage skriver Lundberg att han hyser större sympati med dem som enligt SCB inte skulle klara en oförutsedd utgift på 14 000 kronor. Men det han i övrigt skriver blir ett hån mot just dessa. Jag läser Sveriges Stadsmissioners rapport om materiell fattigdom som fördubblats 2024 jämfört med 2021. Det innebär människor som inte har råd med näringsriktig mat varannan dag, två par skor eller tillräcklig uppvärmning av bostaden. Enligt Stadsmissionen söker sig allt fler till dem för att få mat. I rapporten intervjuas en ensamstående undersköterska och en arbetslös industriarbetare som får matstöd. Det är om dessa vi journalister måste berätta, även när de inte hör till DN:s målgrupp.

Nathalie Rothschild

Poddproducent

•

Igår 01:28

En gång åkte jag skidor. Det var för cirka två veckor sedan. Jag blir inte jätteledsen om jag aldrig behöver göra om det. Men å andra sidan, vad gör man inte för sina barns skull? De måste ju få uppleva fjäll och helst också alper. Jag har förstått att man kan bli orosanmäld om man nekar sina barn den upplevelsen. Och jag har också förstått att den inte går att mäta i pengar. Men Soldatens ärtsoppa? Nej, där går gränsen.

Göran Fröjdh

Reporter

•

26 Feb 21:21

Underhållande observation av medieparnassens kamp för att få vardagspusslet att gå ihop med ynka 60 000 i månadslön. Men med det sagt kostar det att bo i huvudstaden, i alla fall om man inte tillhör den priviligierade elit som haft turen att ha föräldrar/farföräldrar med hyresreglerad innerstadslägenhet. Och den som vill köpa sig till ett vanligt svennigt villaliv på mindre än en timmes pendelavstånd från city behöver uppemot två Lundbergslöner för att slippa njurförsäljning. (Bara att parkera Teslan på gatan mellan Åre-resorna kostar 20 000 om året, och då har man inte ens sin egen plats.)

Erik Högström

Fördjupningsredaktör

•

26 Feb 20:56

Även om jag skriver detta från sportlovssemester (dock det mer frugala Kungsberget) så kan jag identifiera mig med Patrik Lundberg. Det är något sjukt i att en medelålders journalist med en okej karriär inte kvalar in i gruppen som självklart kan åka en vecka till Sälen på sportlovet. Vem kan då göra det? Vad är det för groteskt samhälle vi har skapat? Och man kan inte ens klaga utan att bli förlöjligad.

Widar Andersson

Skribent

•

26 Feb 18:22

Så kul och klokt. Jenny Strindlöv sätter fingret på ett klassiskt faktum: Det är mer tokigt att låtsas vara arm än att låtsas vara välbeställd. Har man hyggliga inkomster så kan man förstås åka till fjällen om man vill. Men om man inte vill åka till fjällen så är det förstås helt ok. Men skyll inte på din armhet. Min tanke går till Janne Josefsson. Uppdrag Granskning i SVT gjorde ett bra program om fattigdom. Janne J besökte en mor som under idogt cigarettrökande beklagade att hon inte hade pengar till mat åt sina barn. ”Men du har pengar nog till cigaretter? frågade Josefsson. En bra fråga. Att ha det armt är inget som befriar en från moraliska överväganden. Och det är samma sak med att ha det välbeställt. Vilket förstås DN: s krönikör borde tänkt på.

Tankar

Anna-Karin Wyndhamn

Författare

•

26 Feb 21:23

Åh, vad detta gör mig trött och missmodig. Hur många normkritiska satsningar tål skolan? Länge var Skolverket hovleverantör av normkritiskt perspektiv på allt och intersektionella fortbildningar für alle. De har taggat ner aktivismen nu, men vad hjälper det när kommunpolitiker fortsätter tro (det här handlar verkligen om tro och övertygelse) på antirasistisk utbildning som allena saliggörande.

Tankar

Federico Moreno

Reporter

•

26 Feb 19:29

När jag läser ABF:s ansökan slås jag av att man skriver att eidfirandet i Malmö ska vara helt alkoholfritt. Kommunen har fått kritik för att sekularisera den muslimska högtiden, men så långt vill inte ABF sträcka sig. När jag talar med personer som är aktiva inom det muslimska civilsamhället och i församlingar får jag höra att kommunens eidfirande uppfattas som ett jippo, snarare än som en muslimsk högtid. Många håller säkert med. Samtidigt bör man vara försiktig med att tro att det bara finns ett muslimskt synsätt. Det gör det förstås inte – på samma sätt som det inte finns bara ett synsätt på alkohol i den muslimska världen. Synen är inte densamma i Saudiarabien och Afghanistan som i Turkiet, Albanien och Tunisien. De muslimska organisationerna verkar generellt vara tacksamma för att kommunen vill stötta firandet, men upplever samtidigt att Socialdemokraterna utnyttjar den islamiska högtiden för att vinna röster.

Tankar

Erik Högström

Fördjupningsredaktör

•

Igår 07:15

Jag tyckte att Magdalena Anderssons bok var bland det sämsta jag har läst. Ni kan läsa mer här: https://kvartal.se/erikhogstrom/artiklar/varfor-forsoker-andersson-lura-oss-att-hon-ar-osmart/cG9zdDozMjI5NQ Men att Socialdemokraterna är så stabila i opinionen är faktiskt imponerande. När gamla maktpartier faller igenom totalt i andra europeiska länder så står de kvar på runt 35 procent. Varför tror ni de lyckas så väl?

Tankar

Jenny Strindlöv

Samhällsredaktör

•

26 Feb 08:24

Utan att ursäkta något får man komma ihåg att den tid och det rum Simone de Beauvoir och Jean Paul Sartre levde i var något helt annat än det vi ser med Epstein och Maxwell idag. Synen på den sexuella frigjordheten i Frankrike på 70-talet hade gått så långt att en rad intellektuella – däribland Sartre och Beauvoir – 1977 gick ut i tidningen med ett upprop om att tillåta sexuella relationer med barn under 15 år. Detta som en protest efter att tre män gripits för sexualbrott mot 12 och 13-åringar. Nog för att svenska kulturarbetare älskar sina upprop, men blotta tanken på att någon enda av dem skulle gå ut på DN Debatt för att protestera mot orättvisan i att vuxna män och kvinnor inte får ligga med 12-åringar är… bisarr.

Tankar

Nathalie Rothschild

Poddproducent

•

25 Feb 19:52

Påminns om att Margaret Thatcher fick öknamnet ”Thatcher, Thatcher, milk snatcher” av oppositionen och i pressen när hon som utbildnings- och forskningsminister på tidigt 70-tal drog in på gratis skollunchmjölk för barn mellan 7 och 11 år. Några år tidigare hade Labour redan dragit in på mjölken för äldre skolbarn — googlade mig nu till att det var Edward Short som låg bakom det beslutet. Tydligen kom ingen på nåt kul rim på hans namn. Short kallade dock Thatcher’s beslut för ”elakt och ovärdigt”.

Tankar

Tankar

Linda Shanwell

Reporter och redaktör

•

25 Feb 18:13

Tanken på att natthimlens skönhet snart kan förstöras, och att satelliter kan ta över platsen för stjärnorna, känns sorglig. Jag har inget emot teknik – men det vore fint om natthimlen fick förbli något som inte helt präglas av Elon Musks och andras projekt.

Tankar

Jenny Strindlöv

Samhällsredaktör

•

25 Feb 12:47

Att muslimska elever är de med mest negativa attityder till judar och hbt-personer kommer väl inte som en direkt överraskning. Det som däremot förvånar mig är att muslimska elever skulle vara de med mest negativa attityder till samer – så till den grad att Malmö därför sticker ut i negativa attityder till just den gruppen. Vad kan det bero på?

Erik Högström

Fördjupningsredaktör

•

25 Feb 12:20

Jag har länge haft en känsla av att många, trots att de vet att Sverige har blivit ett mångkulturellt land, inte riktigt förstår vad det innebär i praktiken. Många tänker intuitivt att skolan ser ut ungefär som när de gick i skolan trots att det har skett en stor demografisk förändring. Jag gissar att de kan ligga bakom att folk riskerar att feltolka verkligheten.

Henrik Höjer

Redaktör

•

25 Feb 12:07

Intressant, minst sagt. Den som vill läsa en vetenskaplig studie av liknande slag rekommenderas denna tidigare Kvartaltext på samma tema: "Så ser svenskar och invandrare på gud, sex och våld": https://kvartal.se/henrikhojer/artiklar/sa-ser-svenskar-och-invandrare-pa-gud-sex-och-vald/cG9zdDo3MTY1

Tankar

Staffan Dopping

Poddredaktör

•

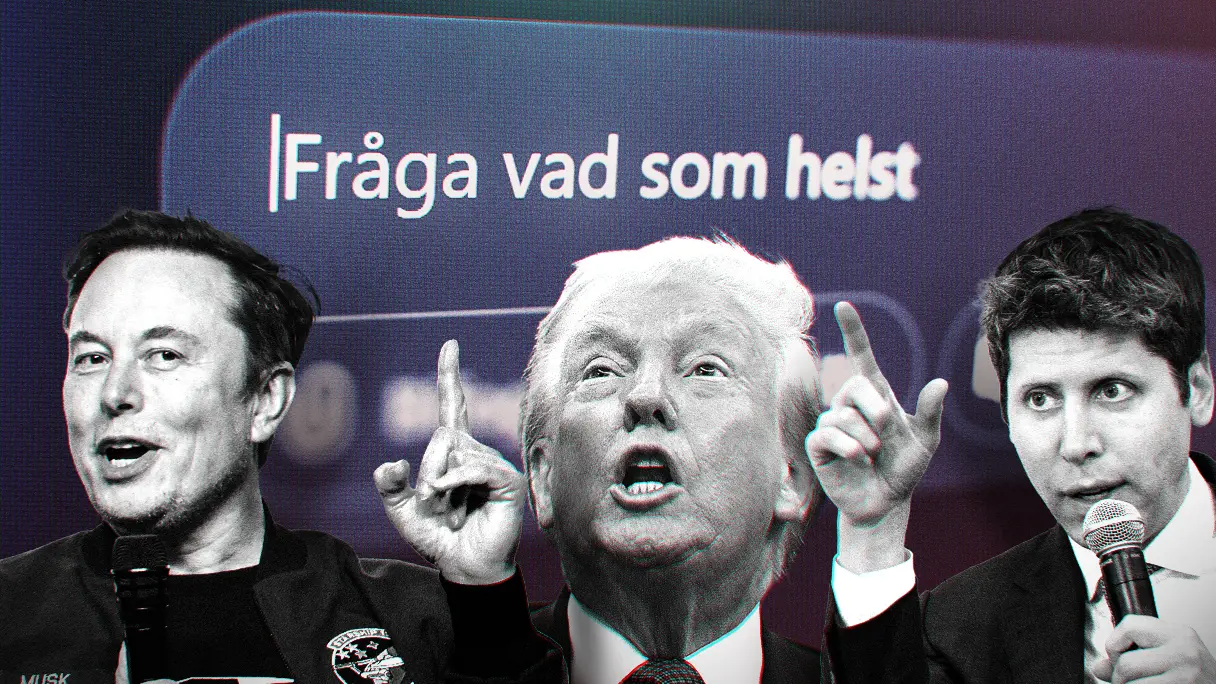

25 Feb 14:38

Apropå att Trump talade rekordlänge nämnde en bekant till mig att det lär finnas belägg för att politiska tal i demokratier tenderar att vara kortare än i diktaturer/auktoritära länder. Det skulle alltså finnas en korrelation mellan anförandelängd och grad av auktoritarianism, och det är förstås inte samma sak som kausalitet. Jag frågade en AI-bot som påminde om att Fidel Castro, Nicolás Maduro och Muammar Qaddafi innehar tidsrekord vid tal i FN. Själv försöker jag hålla mig under 90 minuter när jag håller låda.

Pelle Zackrisson

Reporter

•

25 Feb 10:45

Trumps tal kommer efter några tunga veckor för USA:s president, med bakslaget i HD om tullarna, vikande opinionssiffror och inte minst att frågan om affordability (om vanligt folk upplever att de har råd) har seglat upp som ett allt större problem. Därför var talet riktat främst mot independent-väljare, de som kanske inte gillar Trumps persona, men tycker att hans politik är bra, eller åtminstone att alternativet (Demokraterna) är värre. Jag tycker personligen att Trump är mest underhållande när han improviserar, riffar likt en nutida Don Rickles. Men det vinner inte Trump några independent-röster på. Håller sig Trump i skinnet på sociala medier (ett stort frågetecken) närmaste dygnet kan Vita huset räkna talet som en framgång.

Nathalie Rothschild

Poddproducent

•

25 Feb 07:21

Den noggranna koreografin tycks ha handlat om att beskriva USA som ”great again” med fokus på frågor där Donald Trump och hans administration kammar hem poäng hos sin väljarbas: kulturkrigen, invandringen och säkerheten vid gränsen samt brott och straff och jobbskapande som gynnar arbetarklassen. Föga förvånande vändes fokus bort från begrepp som ICE, Epstein och ”forever wars”. Och när Trump bad de som höll med honom att stå upp så visste han säkerligen att han skulle skapa ett viralt ögonblick då demokrater som Ilhan Omar och Rashida Tlaib satt kvar i sina stolar i stället för att bejaka uttalandet: ”Den amerikanska regeringens främsta plikt är att skydda amerikanska medborgare, inte illegala invandrare.”

Tankar

Linda Shanwell

Reporter och redaktör

•

25 Feb 08:56

Att diagnoser och medicin hjälper många är sant. Men när allt fler svårigheter tolkas som diagnoser finns en risk att vi börjar medicinera bort sådant som är mänskligt. Jag tänker till exempel på ADHD-medicin, som trots allt är ett centralstimulerande preparat. Därför är det inte konstigt att många upplever att de mår bättre eller fungerar bättre av det. Men att något får oss att må bättre betyder inte automatiskt att det är rätt lösning på det som skaver.

Tankar

Göran Fröjdh

Reporter

•

25 Feb 10:58

Den så kallade elmarknaden – som har väldigt lite gemensamt med en ”marknad” – blir alltmer bisarr. Trots att alla politiker pratar sig varma om elektrifiering som ett sätt att nå klimatmålen, finns det ingen produkt som är så hårt beskattad som just el. 55 procent av elräkningen är skatter (det är till och med moms på elskatten). Samtidigt räknas elskatten upp med inflationen varje år (förutom 2026 då den faktiskt sänktes, om än tillfälligt). Frågan är då, om meningen är att vi ska använda mer el, vad är syftet att skatta ihjäl oss? Det var inga problem att sänka bensin- och dieselskatten? Fast tanken är kanske att folk ska värma sig ute i bilen under svinkalla vinterdagar.

Matilda Berg

25 Feb 10:30

Jag går runt med en konstant känsla av att tillvarons komplexitet ökar, på alla plan. (Den är jag inte ensam om, jag vet.) Men sällan blir det så tydligt som när det gäller frågor kring el och energi. Måste vi be om AI-stöd för att hantera de enklaste vardagsrutinerna på ett rationellt sätt? Är det rimligt?

Tankar

Henrik Höjer

Redaktör

•

25 Feb 06:13

Konflikten om islam är av allt att döma här för att stanna. Kan även rekommendera min artikelserie från våren 2024 om Ruud Koopmans forskning. Han tar sig an frågan om elefanten i rummet: Varför det är så svårt att uppnå demokrati och mänskliga rättigheter inom så gott som alla länder där muslimer är i majotitet - här är första delen: https://kvartal.se/henrikhojer/artiklar/man-kan-vara-islamkritisk-utan-att-vara-islamfientlig/cG9zdDoxMDgxNg

Tankar

Jesper Andersson

Poddproducent

•

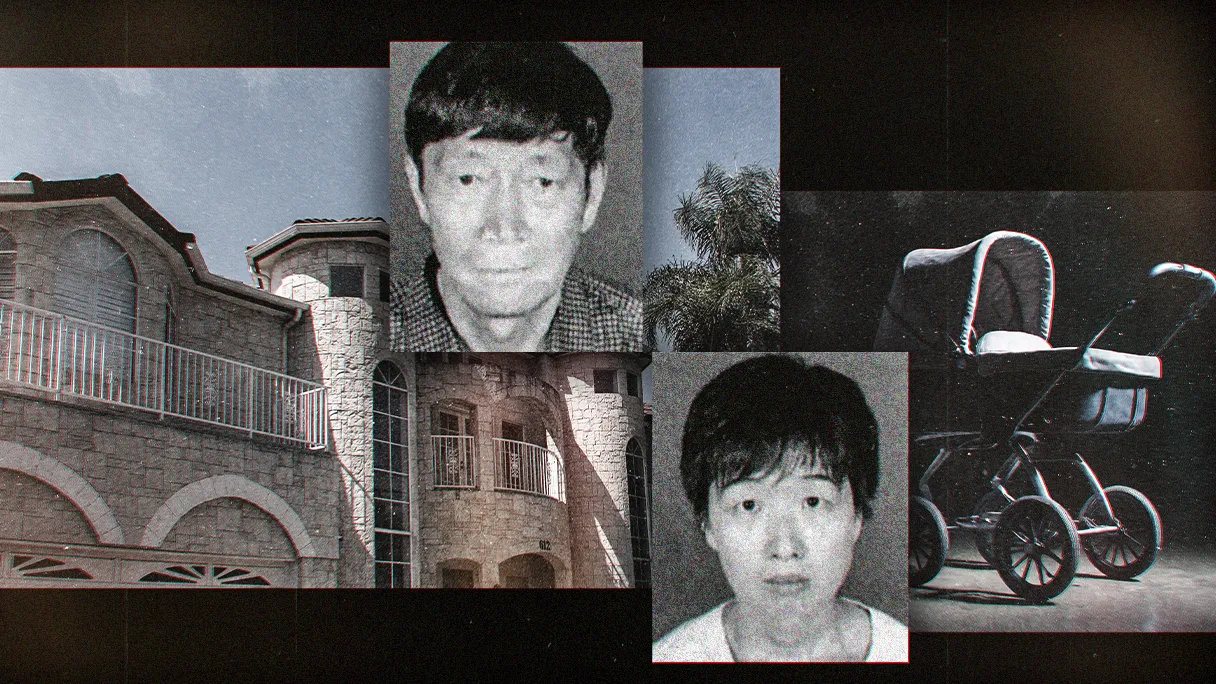

24 Feb 17:17

Det som slår mig varje gång jag går in på Dumpen är hur medvetna många ”gäddor” är när de chattar med vad de tror är ett barn. De nämner Dumpen i chatten, ibland i en lätt skämtsam ton. Ändå slutar de upp på någon parkering i hopp om att få med sig ett barn hem - och får sina liv raserade.

Tankar

Henrik Höjer

Redaktör

•

24 Feb 06:16

Idag är det fyra år sedan Ryssland anföll Ukraina, och Polen är ett av de länder som reagerat starkast - genom egen rustning och stöd till grannlandet Ukraina. Polen är ju också ett land som historiskt har lidit stort av Moskvas krig. Polen har också en snabbt växande ekonomi - reallönerna har mer än fördubblats sedan år 2000. I Sverige har de ökat cirka 20 procent. Polens löner har visserligen ökat från ett lågt läge, men ibland är riktning viktigare än position. Så - räkna med Polen framöver. Jag själv har varit i Polen otaliga gånger, senast i augusti, och gillar skarpt vårt stora och allt mäktigare grannland i söder!

Tankar

Erik Högström

Fördjupningsredaktör

•

23 Feb 14:07

Det är spännande att följa hur den här typen av ”enskilda case”-journalistik har kommit tillbaka. Det var väldigt vanligt förr, sen har det haft en ganska lång lågkonjunktur där knappt några medier har publicerat den typen av berättelser. Detta gäller ju inte bara utvisningsärenden. Historier om folk som får konstiga saker i produkter de köper, eller som är kränkta av olika företeelser blev också mindre vanligt under en period. Ingen vill hamna på sajten https://www.lokaltidningsbesvikelse.se/. Men allt går ju i cykler.

Widar Andersson

Skribent

•

23 Feb 13:25

Bra och faktatung genomgång. Jag vill inte i första hand kalla det som SVT och SR och de stora privata mediehusen gör, för ”kampanjjournalistik” mot SD/M. (Även om det flitiga användandet av begreppet ”tonårsutvisningar” är över gränsen) Däremot är det ett journalistiskt haveri vi åser. SOM-institutet vid Göteborgs universitet visade nyligen i sin omfattande förtroendemätning av media att det den svenska allmänheten litar allra minst på är medias rapportering om invandring. Ett misstroende som folk har fog för. En del journalister jag talat med ser helt enkelt inte hur sneda vinklar de jobbar med. De ser sin uppgift som att ”granska makten” och stå på den ”utsatta” människans sida. Och då blir den som ska utvisas automatiskt ett skyddsvärt offer. Och då ursäktas ett massivt utelämnande av omständigheter som om de ingick i rapporteringen skulle ge en bredare, mer sann och relevant beskrivning av vad som sker. Som sagt, ett haveri som bygger murar mot vanligt folk.

Tankar

Erik Högström

Fördjupningsredaktör

•

23 Feb 20:44

Frågan om surrogatmödraskap är verkligen svår. Personligen ser jag rätten att ingå frivilliga avtal och värdet av att fler barn kommer till världen, samt att ofrivillig barnlöshet kan få en lösning, som tungt vägande argument för. Denna skräckhistoria ska nog inte ses som särskilt representativ.

Tankar

Nathalie Rothschild

Poddproducent

•

24 Feb 15:51

För den generation som växer upp med AI-kompisar som en självklar del av vardagen kommer det inte finnas det något före och efter som skapar kritisk distans. På samma sätt som många unga idag inte vet hur det är att leva utan att dela med sig av sitt privatliv på nätet. Insikterna om nackdelarna med sociala medier växer just nu. Kanske finns det något att lära från den erfarenheten i relation till AI, så att man om några år slipper säga "det är lätt att vara efterklok"?

Tankar

Göran Fröjdh

Reporter

•

23 Feb 18:27

LKAB har i flera år försökt få igång brytning av den stora Per Geijer-malmen i Kiruna, som pekas ut som en av Europas största fyndigheter för sällsynta jordartsmetaller. Problemet är bara att gruvverksamheten inkräktar på de renbetesmarker som används av Gabna sameby under sommartid. I december avbröt samebyn samverkansavtalet med gruvjätten. ”Statliga gruvbolaget LKAB vill producera konfliktmineraler på urfolksmark utan samtycke och med smulor i ersättning…” hette det i Gabnas pressmeddelande. (NSD 1/12) Så det lär nog bli fortsatt brytning i Kongo ett tag till.

Linda Shanwell

Reporter och redaktör

•

23 Feb 08:35

Läsvärd text. Den här sortens utnyttjande av människor hade varit otänkbart i ett västerländskt land. Att det kan fortsätta i Kongo säger något obehagligt om vilka liv som väcker vår upprördhet, och vilka som passerar utan större rubriker. Inte minst när det sker i den gröna omställningens namn.